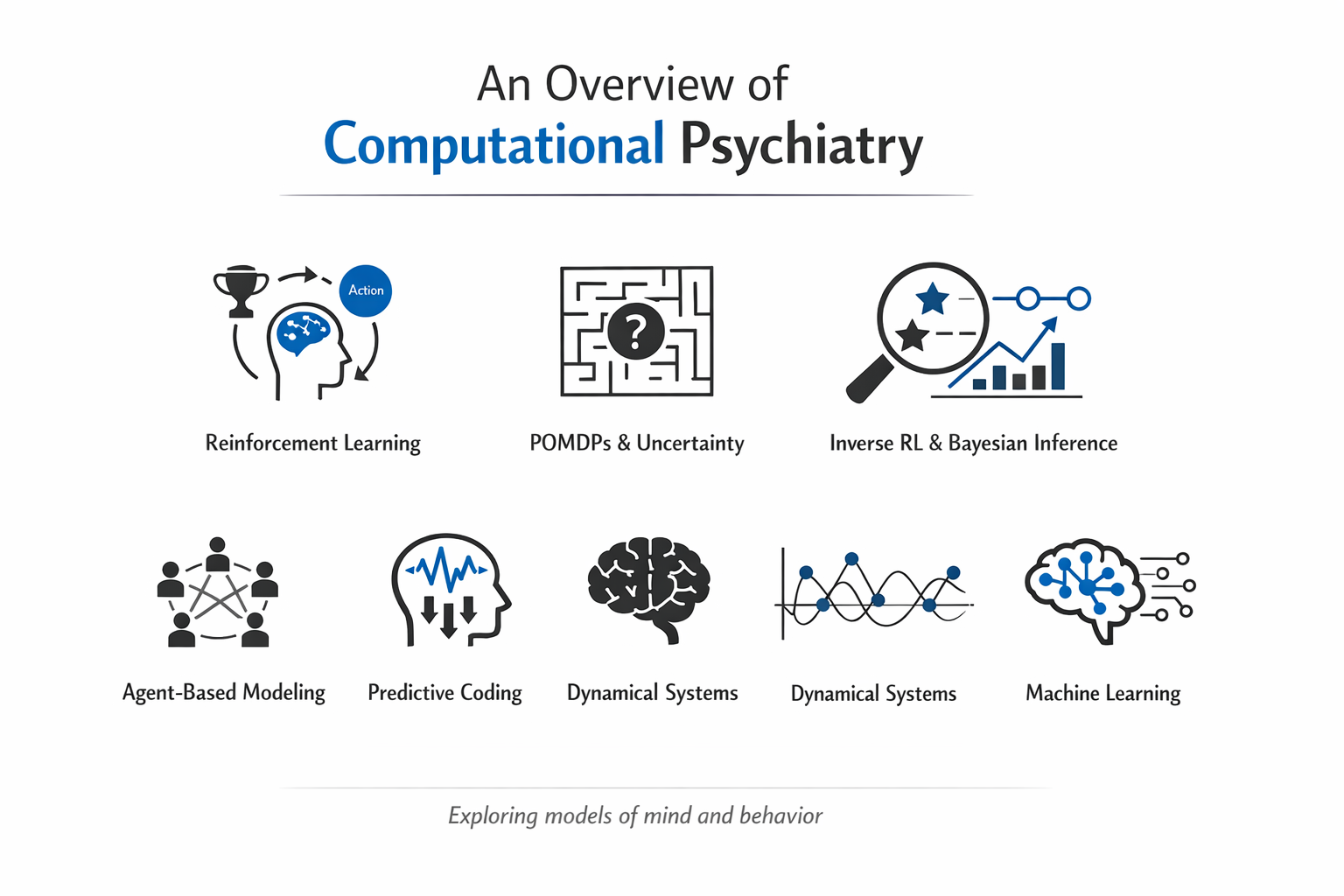

An overview of computational psychiatry

Computational psychiatry tries to describe mental health problems in terms of “computations” the brain might be carrying out—how it learns from outcomes, updates beliefs, and chooses actions—so that symptoms can be connected to mechanisms rather than just checklists. The hope is not to replace clinical judgment, but to add a layer of formal, testable explanation that can sometimes clarify why two people with the same diagnosis look very different in daily life. In practice, these models link what can be observed (choices in tasks, symptom ratings, neural signals) to latent processes (like reward sensitivity or belief updating). That said, the field sometimes risks overselling “precision”: a clean parameter estimate in a lab task may not map neatly onto messy real-world experiences like breakup-driven insomnia or job-loss stress. This is a first post in series of posts where we discuss different approaches and methodologies used in computational psychiatry.

Reinforcement learning and decision-making

Reinforcement learning (RL) provides a family of models describing how agents learn to select actions based on past rewards and punishments. In these models, the agent updates expectations about outcomes when reality deviates from prediction, producing a reward prediction error signal that has clear analogues in dopaminergic brain activity. In depression, RL models have been used to formalize anhedonia and motivational deficits as changes in reward sensitivity, learning rate, or beliefs about controllability. Some work suggests that depressed individuals may underweight positive feedback and over‑generalize negative experiences, capturing phenomena like learned helplessness as altered value estimates for actions and outcomes.

Addiction research uses RL to characterize the shift from goal‑directed (model‑based) control to habitual (model‑free) responding, where drug cues continue to drive behavior despite mounting negative consequences. Models in this area often focus on how drugs distort dopamine‑encoded prediction errors and how this biases learning toward drug‑related actions and cues. More recent work extends simple model‑free formulations by combining them with latent‑state or latent‑cause inference, allowing the model to represent persistent internal motivational states (such as craving) that shape decisions across contexts. These hybrid models appear better suited to capturing phenomena like context‑dependent relapse or sudden shifts in behavior after periods of abstinence.

POMDPs and decision-making under uncertainty

Partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs) model decision‑making when the true state of the environment is uncertain and must be inferred from noisy observations. Formally, a POMDP can be described by a tuple including states, actions, transition probabilities, rewards, observations, and observation probabilities, together with a discount factor that determines the weight of future outcomes. Rather than directly observing the state, the agent maintains a belief distribution over possible states and updates it in light of new evidence. This structure aligns well with psychiatric contexts where people must infer threats, social intentions, or bodily states from ambiguous information. In anxiety disorders, POMDP‑style models can capture persistent overestimation of threat: the belief state remains biased toward danger, supporting hypervigilance and avoidance even when objective risk is low. Depression may involve pessimistic belief updating, where low‑probability negative outcomes get overweighted relative to positive possibilities, reinforcing withdrawal and hopelessness. In psychosis, POMDPs and related Bayesian state‑estimation models have been used to formalize “reality distortion” as an imbalance between prior expectations and sensory evidence. When priors are granted abnormally high precision relative to incoming data, the model can generate delusional interpretations of ambiguous stimuli; when sensory prediction errors are assigned aberrant salience, hallucinations can emerge from noisy internal signals.

Inverse reinforcement learning and Bayesian estimation

Inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) inverts the usual RL problem: given observed behavior, it seeks to infer the reward structure and preferences that would make that behavior rational within a task. This is particularly useful in psychiatry, where patients’ motivations and value functions may differ qualitatively from those of healthy controls, but cannot be observed directly. Bayesian implementations of RL and IRL, often fit with probabilistic programming languages such as Stan, allow researchers to capture individual variability via hierarchical priors and to quantify uncertainty about parameters. This supports richer “computational phenotyping,” where traits like reward sensitivity, risk preferences, or controllability beliefs are treated as latent parameters that vary across the population and may relate to brain measures or treatment outcomes.

Recent semiparametric IRL approaches applied to major depressive disorder (MDD) use hierarchical Bayesian models to estimate both learning dynamics and reward sensitivity across individuals. Guo and colleagues showed that MDD and control groups can display similar learning rates while differing markedly in the shape of their reward sensitivity functions, which were nonlinear and attenuated in patients. This challenges the idea that depression necessarily involves a primary learning deficit, instead highlighting alterations in how rewards are valued.

Agent-based modeling and population dynamics

Agent‑based models (ABMs) simulate many interacting individuals (“agents”) embedded in an environment, each following simple rules, to study how individual‑level processes give rise to population‑level patterns. In computational psychiatry, ABMs are used to explore how symptoms, treatment access, and social context interact over time across communities. Agents can be endowed with internal psychological dynamics (such as symptom trajectories or learning rules) and placed within social networks that transmit information, norms, or support. This allows simulation of how changes in one person’s symptoms—say after starting cognitive behavioral therapy—might ripple through their support network to influence others’ trajectories, or how service redesign affects wait times, adherence, and overall burden on a mental health system. Multi‑scale ABMs can link medical data (e.g., diagnosis rates, treatment capacities) with behavioral rules to test hypothetical policy changes before real‑world implementation. These models are especially powerful for studying questions that are hard to tackle in randomized trials, such as how economic shocks, digital interventions, or stigma might shape the long‑term prevalence of disorders. That said, they require strong assumptions about agents and environments, so careful validation against empirical data is essential.

Predictive coding and the Bayesian brain

As we have seen in our series of posts about the Free Energy Principle and Active inference, the predictive coding and Bayesian brain frameworks propose that the brain constantly generates predictions about sensory inputs and minimizes prediction errors by updating beliefs or acting on the world. In these accounts, perception, action, and even emotion emerge from hierarchical generative models that balance prior expectations against incoming evidence, weighted by their relative precision. In our post about autism we mentioned that predictive coding theories suggest altered precision assignments may lead to overly precise low‑level sensory predictions and insufficient weighting of higher‑level context. This can help explain both hypersensitivity to sensory detail and difficulty using broader context to interpret ambiguous stimuli, as described in work on “precise minds in uncertain worlds.” In schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, models attribute positive symptoms to mis‑tuned precision across cortical hierarchies, where over‑precise priors can drive delusions and aberrant assignment of salience to neutral events, while under‑ or mis‑precise sensory predictions contribute to hallucinations. Active inference extends predictive coding by treating action selection as another route to minimizing expected prediction error or free energy, often formalized in POMDP‑like terms. This provides a unified setting in which perception, decision‑making, and action are modeled under a single Bayesian principle, and has inspired work on motor symptoms, interoception, and social cognition in psychiatry.

Temporal dynamics and dynamical systems

Most computational models treat parameters as static—a person’s reward sensitivity or learning rate is estimated once and assumed constant. Yet psychiatric symptoms fluctuate from day to day, sometimes hour to hour, and the relationships among symptoms can shift across timescales. Dynamical systems approaches use differential equations to capture how variables evolve continuously in time, allowing researchers to model symptom trajectories, attractor states, and sudden transitions (bifurcations) that occur when environmental stressors or interventions push someone across a threshold. A dynamical model might track interactions among mood, rumination, sleep, and social contact, with each variable influencing the others according to differential equations that specify rates of change. Time-varying network models extend this idea by estimating how the strength and direction of these associations change over weeks or months. In one study of patients with recurrent depression, daily self-report data revealed marked differences between individuals: some showed stable symptom networks over months, while others exhibited rapid shifts in how symptoms influenced each other within weeks. This suggests that the same diagnosis can hide very different underlying dynamics, with implications for when and how to intervene.

These models raise practical questions about timescales. Should we capture mood variations every 15 minutes, once per day, or weekly? Finer temporal resolution risks drowning signal in noise—every minor reaction to a text message—while coarser bins may miss clinically meaningful fluctuations like morning versus evening mood in cyclothymia. There is no universal answer; the right timescale depends on the disorder and the question. Dynamical models also demand longer stretches of data than traditional cross-sectional studies, which can be burdensome for participants. Still, the payoff is substantial: by mapping how symptoms interact and change, these approaches can identify early warning signals of relapse, critical periods for treatment, and personalized intervention targets that static models overlook.

Machine learning and data-driven models

In parallel with mechanism‑driven models, computational psychiatry increasingly uses machine learning (ML) to extract patterns from high‑dimensional data such as neuroimaging, genetics, and digital traces. Approaches include deep learning for brain images, clustering methods to discover symptom subtypes, and natural language processing to detect linguistic markers of risk in speech or social media. ML models often excel at prediction but can be hard to interpret, whereas mechanistic models (RL, POMDPs, predictive coding) sacrifice some predictive power for explanatory insight. Hybrid strategies are emerging: ML might identify subgroups of patients with distinct trajectories, while mechanistic models characterize the computational profiles of each subgroup. Semi‑supervised and multitask learning approaches can leverage limited labeled clinical data alongside large unlabeled digital datasets, improving prediction while retaining some structure for interpretation. Ethical and practical considerations loom large—data quality, algorithmic bias, transparency, and the risk of over‑reliance on black‑box predictions all pose challenges for clinical deployment. Frameworks for ethical decision‑making in AI for mental health emphasize stakeholder involvement, explanation tailored to patients, and early attention to implementation barriers, not just model performance.

Future directions and conclusion

Computational psychiatry now has a rich toolkit spanning reinforcement learning, POMDPs, IRL, agent‑based models, predictive coding, dynamical systems. These approaches promise more precise, mechanism‑informed psychiatry, where diagnoses and treatments are guided not only by symptom counts but by quantified alterations in learning, valuation, belief formation, and temporal dynamics. Realizing this promise requires careful attention to ethics, education, and infrastructure. Key challenges include protecting privacy while analyzing sensitive multimodal data, mitigating bias in training sets, ensuring that models generalize beyond narrow cohorts, and supporting clinicians in interpreting and communicating computational outputs. Progress will depend on collaboration among computational scientists, clinicians, patients, and ethicists, with a focus on tools that are not only accurate but also trustworthy, equitable, and clinically useful. As the field matures, the questions shift from “Can we model this?” to “Should we model this, and for whom?”. The most useful advances will likely come not from ever-more sophisticated algorithms, but from careful attention to context, stakeholder needs, and the messy realities of implementing formal models in healthcare systems that are already stretched thin. Computational psychiatry has opened doors; walking through them will require humility, interdisciplinary dialogue, and a willingness to test ideas in the real world where patients live.

References

-

Adams, R. A., Huys, Q. J. M., & Roiser, J. P. (2016). Computational psychiatry: Towards a mathematically informed understanding of mental illness. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 87(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-310737

-

Adams, R. A., Meyer, S., Smith, R., & et al. (2025). Computational psychiatry: A bridge between neuroscience and clinical practice. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences Reports, 4, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/pcn5.41

-

Adolphs, R., & Montague, P. R. (2024). Neurocomputational underpinnings of suboptimal beliefs in mental illness. Conference on Cognitive Computational Neuroscience (CCN 2025) Proceedings. https://pehlevan.seas.harvard.edu/sites/g/files/omnuum6471/files/2025-07/Kumar_et_al_CCN_Proceedings_2025.pdf

-

Barto, A. G., Sutton, R. S., & Anderson, C. W. (1998). Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT Press. https://web.stanford.edu/class/psych209/Readings/SuttonBartoIPRLBook2ndEd.pdf

-

Fusar-Poli, P., Correll, C. U., Arango, C., & et al. (2022). Ethical considerations for precision psychiatry: A position statement from the European Brain Research Area. European Psychiatry, 65(1), e57. https://www.ebra.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/PSMD_Fusar-Poli-et-al.-2022-Ethical-considerations-for-precision-psychiatry-A.pdf

-

Huys, Q. J. M. (2021, November 29). Bayesian hierarchical reinforcement learning in psychiatry. In Computational psychiatry (blog). https://bruno.nicenboim.me/2021/11/29/bayesian-h-reinforcement-learning/

-

Khaleghi, A., & et al. (2022). Computational neuroscience approach to psychiatry: A review on theory-driven approaches. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 20(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2022.20.1.26

-

Maia, T. V., & Frank, M. J. (2011). From reinforcement learning models to psychiatric and neurological disorders. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 154–162. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2866366/

-

Montague, P. R., Dolan, R. J., Friston, K. J., & Dayan, P. (2012). Computational psychiatry. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.018

-

Możaryn, J. F., & et al. (2025). Computational psychiatry: A bridge between neuroscience and clinical practice. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1181526. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11815263/

-

Samson, R. D., Frank, M. J., & Fellous, J.-M. (2010). Computational models of reinforcement learning: The role of dopamine as a reward signal. Cognitive Neurodynamics, 4(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11571-010-9109-x

-

Seriès, P. (n.d.). A primer on computational psychiatry. School of Informatics, University of Edinburgh. https://homepages.inf.ed.ac.uk/pseries/CPPrimer/CPprimer-submitted.pdf

-

Wang, X.-J., & Krystal, J. H. (2014). Computational psychiatry. Neuron, 84(3), 638–654. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4255477/