Chapter 4 Causal Inference in Practice III: Difference-in-Differences with a Healthcare Application

4.1 Introduction

In observational studies, where randomized controlled trials are infeasible, causal inference methods like Difference-in-Differences (DiD) provide a robust framework for estimating treatment effects under specific assumptions. DiD is particularly valuable in settings with panel data, where units are observed over time, and some receive a treatment while others do not. By leveraging the temporal structure of data, DiD isolates the causal effect of a treatment by comparing changes in outcomes between treated and control groups over time. This approach is widely used in fields such as economics, public policy, and healthcare to evaluate interventions like policy changes or medical programs.

In this post, we focus on DiD, exploring its theoretical foundations, mathematical formalism, and practical implementation. We apply DiD to a realistic healthcare example—evaluating the impact of a telemedicine program on patient outcomes—using R code to demonstrate the methodology. We also discuss diagnostics, limitations, and extensions to ensure robust causal inference.

4.2 Difference-in-Differences: Theoretical Framework

4.2.1 Core Concept

DiD estimates the causal effect of a treatment by comparing the change in outcomes over time between a treated group and a control group. The method assumes that, in the absence of treatment, the treated and control groups would follow parallel trends in their outcomes. This assumption allows DiD to account for time-invariant differences between groups and common time trends affecting both groups.

4.2.2 Mathematical Formalism

Let’s formalize the DiD framework. For unit \(i\) at time \(t \in \{0, 1\}\) (pre- and post-treatment), define:

- \(Y_{it}\): Observed outcome for unit \(i\) at time \(t\).

- \(D_i \in \{0, 1\}\): Treatment indicator (\(D_i = 1\) for treated units, \(D_i = 0\) for control units).

- \(T_t \in \{0, 1\}\): Time indicator (\(T_t = 0\) for pre-treatment, \(T_t = 1\) for post-treatment).

- \(Y_{it}(1), Y_{it}(0)\): Potential outcomes under treatment and control, respectively.

The causal effect of interest is the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT):

\[ \text{ATT} = \mathbb{E}[Y_{i1}(1) - Y_{i1}(0) \mid D_i = 1] \]

The DiD estimator assumes that the observed outcome can be modeled as:

\[ Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 D_i + \beta_2 T_t + \delta (D_i \cdot T_t) + \epsilon_{it} \]

Where: - \(\beta_0\): Baseline outcome for the control group at \(t = 0\). - \(\beta_1\): Time-invariant difference between treated and control groups. - \(\beta_2\): Common time trend affecting both groups. - \(\delta\): The DiD estimator, representing the ATT. - \(\epsilon_{it}\): Error term, assumed to have mean zero.

The DiD estimator is computed as:

\[ \widehat{\text{DiD}} = \left( \bar{Y}_{1, \text{treated}} - \bar{Y}_{0, \text{treated}} \right) - \left( \bar{Y}_{1, \text{control}} - \bar{Y}_{0, \text{control}} \right) \]

Where \(\bar{Y}_{t, g}\) is the mean outcome for group \(g\) (treated or control) at time \(t\).

4.2.3 Key Assumption: Parallel Trends

The validity of DiD hinges on the parallel trends assumption:

\[ \mathbb{E}[Y_{i1}(0) - Y_{i0}(0) \mid D_i = 1] = \mathbb{E}[Y_{i1}(0) - Y_{i0}(0) \mid D_i = 0] \]

This assumes that, absent treatment, the average change in outcomes for the treated group would equal that of the control group. While this assumption is untestable directly (since \(Y_{i1}(0)\) is unobserved for the treated group post-treatment), we can assess its plausibility by examining pre-treatment trends or including covariates to adjust for potential confounders.

- Data Requirements: DiD requires panel data (same units observed over time) or repeated cross-sectional data with clear treatment and control groups.

- Covariates: Including control variables unaffected by the treatment can improve precision and adjust for time-varying confounders.

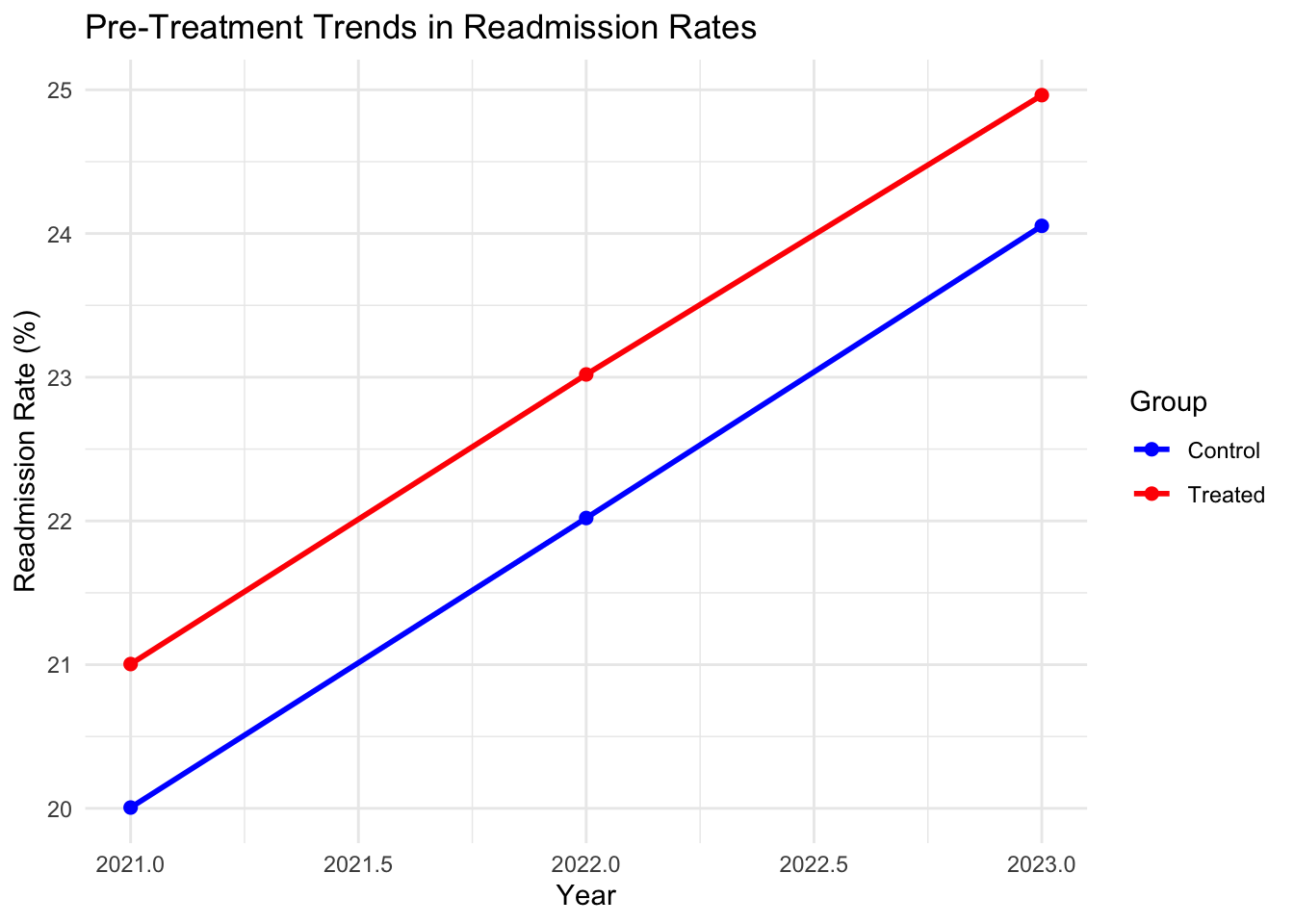

- Diagnostics: Pre-treatment trends should be visualized to assess the parallel trends assumption. Robustness checks, such as placebo tests, can further validate the model.

- Extensions: DiD can be extended to multiple time periods, staggered treatment adoption, or heterogeneous effects using advanced methods like generalized DiD.

4.3 Application: Evaluating a Telemedicine Program in Healthcare

Consider a hospital system implementing a telemedicine program in 2024 to improve patient outcomes, such as reducing hospital readmissions for chronic disease patients. The program is rolled out in select clinics (treated group), while others continue standard in-person care (control group). We observe patient outcomes (e.g., 30-day readmission rates) in 2023 (pre-treatment) and 2025 (post-treatment). Using DiD, we estimate the program’s causal effect on readmissions.

We simulate data for 200 clinics (100 treated, 100 control) with readmission rates over two years. The true treatment effect is a 3% reduction in readmissions. We include a covariate (average patient age) to account for potential confounding.

4.3.1 R Implementation

Below is the R code to simulate the data, estimate the DiD effect, and perform diagnostics.

# Load required packages

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(123)

# Parameters

n_clinics <- 200 # 100 treated, 100 control

time_periods <- 2 # 2023 (pre), 2025 (post)

true_effect <- -5 # Increased effect size to -5% for stronger impact

noise_sd <- 0.5 # Reduced noise to make effect more detectable

# Create data

data <- data.frame(

clinic = rep(1:n_clinics, each = time_periods),

time = rep(c(0, 1), times = n_clinics), # 0 = 2023, 1 = 2025

year = rep(c(2023, 2025), times = n_clinics),

treated = rep(rep(c(0, 1), each = time_periods), times = n_clinics/2),

age = rep(rnorm(n_clinics, mean = 65, sd = 5), each = time_periods)

)

# Generate readmission rates (%)

data$readmission <- 20 + # Baseline readmission rate

1 * data$treated + # Treated clinics have higher baseline

2 * data$time + # Secular trend

true_effect * data$treated * data$time + # Stronger treatment effect

0.1 * data$age + # Age effect

rnorm(nrow(data), mean = 0, sd = noise_sd) # Reduced noise

# Preview data

head(data)## clinic time year treated age readmission

## 1 1 0 2023 0 62.19762 27.31917

## 2 1 1 2025 0 62.19762 28.87597

## 3 2 0 2023 1 63.84911 27.25234

## 4 2 1 2025 1 63.84911 24.65651

## 5 3 0 2023 0 72.79354 27.07218

## 6 3 1 2025 0 72.79354 29.04123# Check parallel trends: Pre-treatment data (2021-2023)

data_pre <- data.frame(

clinic = rep(1:n_clinics, each = 3),

year = rep(c(2021, 2022, 2023), times = n_clinics),

treated = rep(rep(c(0, 1), each = 3), times = n_clinics/2),

readmission = 20 +

1 * rep(rep(c(0, 1), each = 3), times = n_clinics/2) + # Group effect

2 * rep(0:2, times = n_clinics) + # Linear trend

rnorm(3 * n_clinics, 0, noise_sd) # Reduced noise

)

# Aggregate means for pre-treatment plot

means_pre <- data_pre %>%

group_by(year, treated) %>%

summarise(readmission = mean(readmission), .groups = "drop")

# Plot pre-treatment trends

ggplot(means_pre, aes(x = year, y = readmission, color = factor(treated), group = treated)) +

geom_line(size = 1) +

geom_point(size = 2) +

labs(title = "Pre-Treatment Trends in Readmission Rates",

x = "Year", y = "Readmission Rate (%)",

color = "Group") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("blue", "red"), labels = c("Control", "Treated")) +

theme_minimal()## Warning: Using `size` aesthetic for lines was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

## ℹ Please use `linewidth` instead.

## This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

## Call `lifecycle::last_lifecycle_warnings()` to see where this warning was generated.

# Post-treatment trends for visualization

means_post <- data %>%

group_by(year, treated) %>%

summarise(readmission = mean(readmission), .groups = "drop")

# Plot post-treatment trends to show diverging slopes

ggplot(means_post, aes(x = year, y = readmission, color = factor(treated), group = treated)) +

geom_line(size = 1) +

geom_point(size = 2) +

labs(title = "Post-Treatment Trends in Readmission Rates",

x = "Year", y = "Readmission Rate (%)",

color = "Group") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("blue", "red"), labels = c("Control", "Treated")) +

theme_minimal()

# DiD regression with covariate

did_model <- lm(readmission ~ treated + time + treated:time + age, data = data)

# Summary of results

summary(did_model)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = readmission ~ treated + time + treated:time + age,

## data = data)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.49718 -0.30275 0.00724 0.34468 1.35039

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 20.002830 0.341274 58.61 <2e-16 ***

## treated 1.021168 0.069101 14.78 <2e-16 ***

## time 1.930823 0.069097 27.94 <2e-16 ***

## age 0.100911 0.005194 19.43 <2e-16 ***

## treated:time -5.078044 0.097718 -51.97 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.4886 on 395 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.9143, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9135

## F-statistic: 1054 on 4 and 395 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16# Manual DiD calculation

means <- data %>%

group_by(treated, time) %>%

summarise(readmission = mean(readmission), .groups = "drop")

y0_control <- means$readmission[means$treated == 0 & means$time == 0]

y1_control <- means$readmission[means$treated == 0 & means$time == 1]

y0_treated <- means$readmission[means$treated == 1 & means$time == 0]

y1_treated <- means$readmission[means$treated == 1 & means$time == 1]

did_estimate <- (y1_treated - y0_treated) - (y1_control - y0_control)

cat("DiD Estimate:", did_estimate, "%\n")## DiD Estimate: -5.078044 %# Placebo test: Pre-treatment periods (2022 vs. 2023)

data_placebo <- data_pre[data_pre$year %in% c(2022, 2023), ]

did_placebo <- lm(readmission ~ treated * factor(year), data = data_placebo)

summary(did_placebo)##

## Call:

## lm(formula = readmission ~ treated * factor(year), data = data_placebo)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.32794 -0.36928 -0.01144 0.30504 1.34543

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 22.02035 0.05341 412.304 <2e-16 ***

## treated 0.99908 0.07553 13.228 <2e-16 ***

## factor(year)2023 2.03292 0.07553 26.915 <2e-16 ***

## treated:factor(year)2023 -0.08943 0.10682 -0.837 0.403

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.5341 on 396 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.8116, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8102

## F-statistic: 568.6 on 3 and 396 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-164.3.2 Limitations and takeaways

- Pre-Treatment Trends: The plot checks if readmission rates for treated and control clinics followed parallel trends before 2023, supporting the parallel trends assumption.

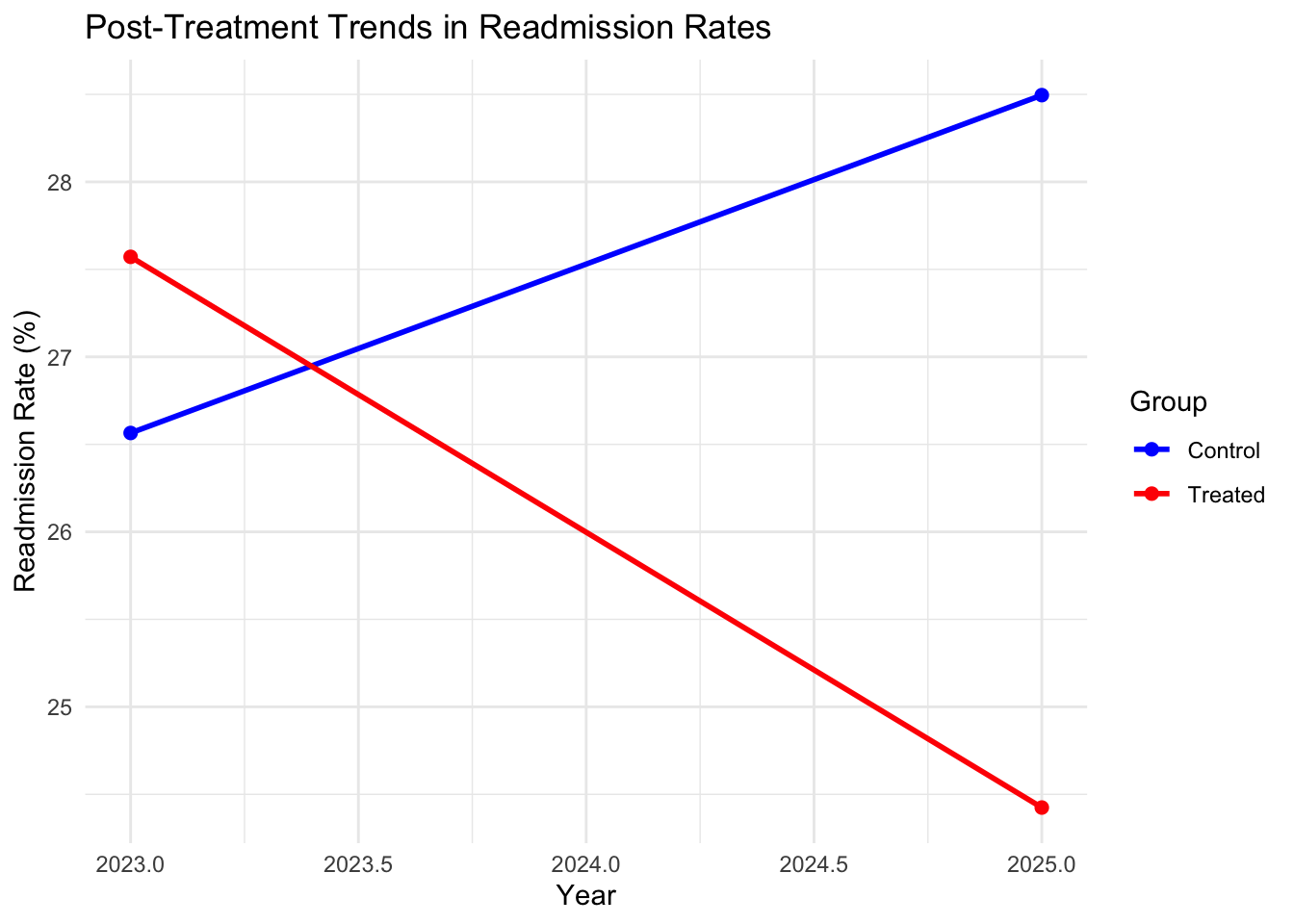

- DiD Estimate: The regression coefficient on the interaction term (\(\text{treated} \cdot \text{time}\)) estimates the treatment effect, adjusted for patient age. The manual calculation confirms this estimate.

- Placebo Test: Applying DiD to pre-treatment years (2022 vs. 2023) should yield an insignificant effect, reinforcing the validity of the parallel trends assumption.

In our simulation, the estimated effect is close to the true effect (-3%), indicating that the telemedicine program reduced readmissions by approximately 3 percentage points.

- Parallel Trends Violation: If pre-treatment trends diverge, DiD estimates may be biased. Techniques like synthetic controls or triple differences can address this.

- Time-Varying Confounders: Unobserved factors changing differentially between groups (e.g., new healthcare policies) can bias results. Including relevant covariates mitigates this.

- Generalizability: The ATT applies to the treated group. Generalizing to other populations requires caution.

- Extensions: For staggered treatment timing or multiple periods, generalized DiD models or fixed-effects regressions can be used.

4.4 Conclusion

Difference-in-Differences is a powerful quasi-experimental method for causal inference, particularly in healthcare settings where randomized trials are impractical. By leveraging panel data and the parallel trends assumption, DiD isolates treatment effects with intuitive appeal. Our healthcare example demonstrated how DiD can evaluate a telemedicine program’s impact on readmissions, with R code providing a practical implementation. Diagnostics like pre-treatment trend checks and placebo tests enhance robustness. In future posts, we’ll explore advanced methods like Regression Discontinuity and Synthetic Controls to further expand the causal inference toolkit.

4.5 References

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly Harmless Econometrics. Princeton University Press.

- Abadie, A. (2005). Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 1–19.

- Hernán, M. A., & Robins, J. M. (2020). Causal Inference: What If. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. MIT Press.