Chapter 3 Markov Decision Processes and Dynamic Programming

3.1 Introduction

Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) constitute a formal framework for modeling sequential decision-making under uncertainty. Widely applied in operations research, control theory, economics, and artificial intelligence, MDPs encapsulate the dynamics of environments where outcomes are partly stochastic and partly under an agent’s control. At their core, MDPs unify probabilistic transitions, state-contingent rewards, and long-term optimization goals. This post explores MDPs from a computational standpoint, emphasizing Dynamic Programming (DP) methods—particularly Value Iteration—for solving them when the model is fully known. We proceed by defining the mathematical components of MDPs, implementing them in R, and illustrating policy derivation using value iteration. A comparative summary of key aspects of DP methods concludes the post.

An MDP is formally defined by the tuple $(S, A, P, R, )$, where:

- $S$: a finite set of states.

- $A$: a finite set of actions.

- $P(s’|s, a)$: the transition probability function—probability of moving to state $s’$ given current state $s$ and action $a$.

- $R(s, a, s’)$: the reward received after transitioning from state $s$ to $s’$ via action $a$.

- $[0,1]$: the discount factor, representing the agent’s preference for immediate versus delayed rewards.

The agent’s objective is to learn a policy $: S A$ that maximizes the expected cumulative discounted reward:

\[ V^\pi(s) = \mathbb{E}_\pi \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t R(S_t, A_t, S_{t+1}) \,\bigg|\, S_0 = s \right] \]

The optimal value function $V^*$ satisfies the Bellman optimality equation:

$$ V^*(s) = {a A} {s’ S} P(s’|s,a)

$$

Once $V^$ is computed, the optimal policy $^$ is obtained via:

$$ ^*(s) = {a A} {s’} P(s’|s,a)

$$

3.2 Constructing the MDP in R

We now implement an environment with 10 states and 2 actions per state, following stochastic transition and reward dynamics. The final state is absorbing, with no further transitions or rewards.

n_states <- 10

n_actions <- 2

gamma <- 0.9

terminal_state <- n_states

set.seed(42)

transition_model <- array(0, dim = c(n_states, n_actions, n_states))

reward_model <- array(0, dim = c(n_states, n_actions, n_states))

for (s in 1:(n_states - 1)) {

transition_model[s, 1, s + 1] <- 0.9

transition_model[s, 1, sample(1:n_states, 1)] <- 0.1

transition_model[s, 2, sample(1:n_states, 1)] <- 0.8

transition_model[s, 2, sample(1:n_states, 1)] <- 0.2

for (s_prime in 1:n_states) {

reward_model[s, 1, s_prime] <- ifelse(s_prime == n_states, 1.0, 0.1 * runif(1))

reward_model[s, 2, s_prime] <- ifelse(s_prime == n_states, 0.5, 0.05 * runif(1))

}

}

transition_model[n_states, , ] <- 0

reward_model[n_states, , ] <- 0Explanation:

This block defines the MDP. We create n_states = 10 with n_actions = 2. The transition probabilities are stored in a 3D array, where the first dimension is the current state, the second is the action, and the third is the next state. Action 1 strongly favors moving forward to the next state (90% chance), while Action 2 introduces more randomness (different probabilities to jump to random states). Rewards are drawn randomly, but reaching the terminal state yields higher rewards (1.0 for Action 1 and 0.5 for Action 2). Finally, the terminal state has no outgoing transitions or rewards, making it absorbing.

We define a function to sample from the environment:

sample_env <- function(s, a) {

probs <- transition_model[s, a, ]

s_prime <- sample(1:n_states, 1, prob = probs)

reward <- reward_model[s, a, s_prime]

list(s_prime = s_prime, reward = reward)

}Explanation:

This function simulates environment dynamics. Given a current state s and action a, it samples the next state s_prime according to the transition probabilities and retrieves the corresponding reward. The function outputs both the next state and the reward, mimicking how an agent would experience interaction with the MDP.

3.3 Value Iteration Algorithm

Value Iteration is a fundamental DP method for computing the optimal value function and deriving the optimal policy. It exploits the Bellman optimality equation through successive approximation.

value_iteration <- function() {

V <- rep(0, n_states)

policy <- rep(1, n_states)

theta <- 1e-4

repeat {

delta <- 0

for (s in 1:(n_states - 1)) {

v <- V[s]

q_values <- numeric(n_actions)

for (a in 1:n_actions) {

for (s_prime in 1:n_states) {

q_values[a] <- q_values[a] +

transition_model[s, a, s_prime] *

(reward_model[s, a, s_prime] + gamma * V[s_prime])

}

}

V[s] <- max(q_values)

policy[s] <- which.max(q_values)

delta <- max(delta, abs(v - V[s]))

}

if (delta < theta) break

}

list(V = V, policy = policy)

}Explanation:

This function implements value iteration. It initializes all state values V to zero and assigns a default policy of choosing action 1. At each iteration, the algorithm updates the value of each state by computing expected returns for all actions (q_values) and taking the maximum. The associated action becomes the new policy for that state. The process continues until the maximum change in values (delta) is below the convergence threshold theta. The function outputs both the value function and the derived policy.

We now apply the algorithm and extract the resulting value function and policy:

## [1] 2 2 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1Explanation:

Here we run the value iteration function and extract the results. The dp_value vector contains the optimal state values, while dp_policy indicates the best action to take at each state. Printing dp_policy gives us a direct mapping from state to optimal action.

3.4 Evaluation and Interpretation

The policy and value function obtained via value iteration provide complete guidance for optimal behavior in the modeled environment. In this setting:

- The forward action (Action 1) is generally rewarded with higher long-term return due to its tendency to reach the terminal (high-reward) state.

- The second action (Action 2) introduces randomness and lower rewards, thus is optimal only in specific states where it offers a better expected value.

Such interpretation emphasizes the Bellman principle of optimality: every sub-policy of an optimal policy must itself be optimal for the corresponding subproblem.

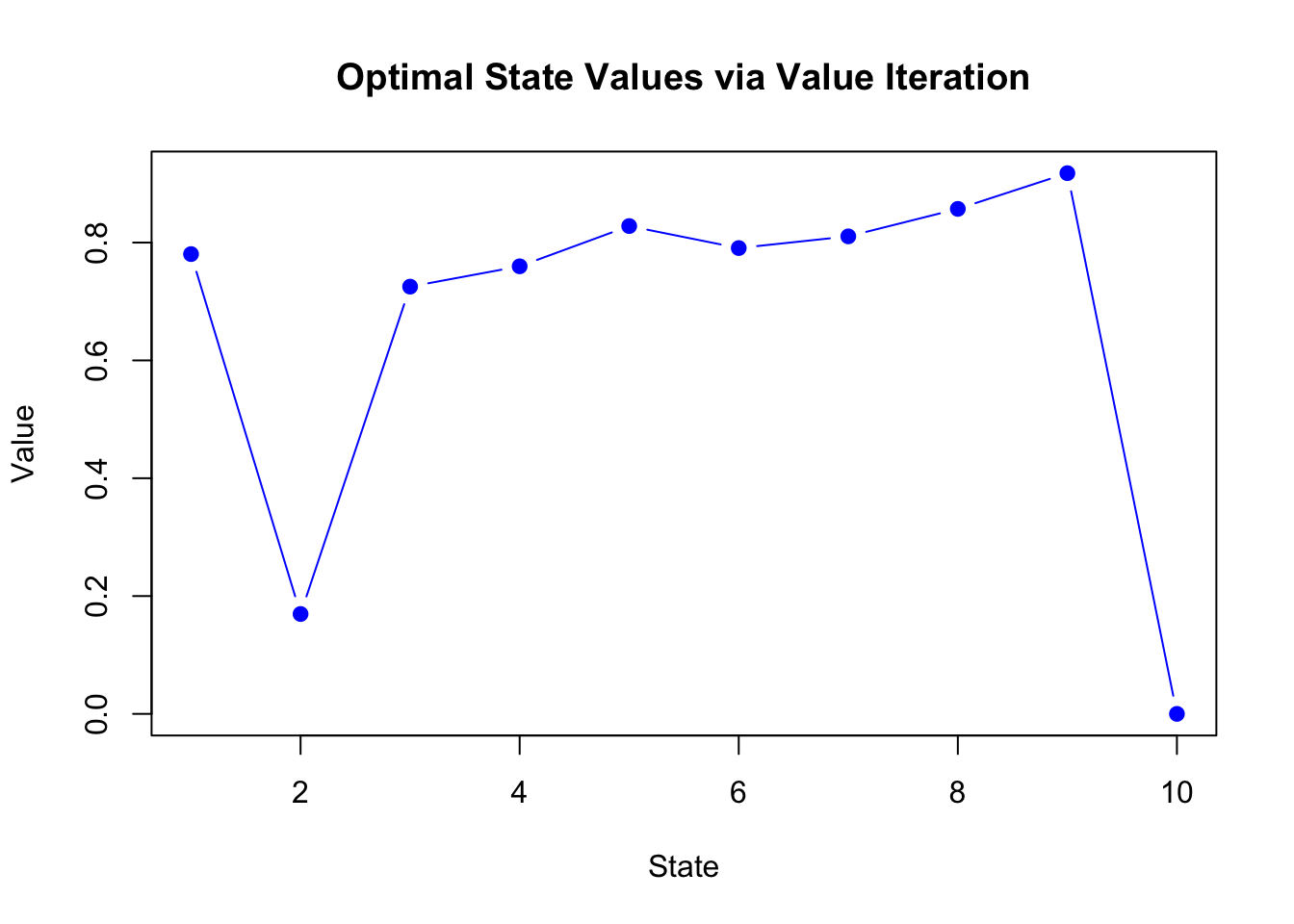

We can visualize the value function:

plot(dp_value, type = "b", col = "blue", pch = 19,

xlab = "State", ylab = "Value",

main = "Optimal State Values via Value Iteration")

Explanation: This plot shows the computed value function across all states. Higher values indicate states with greater expected long-term returns under the optimal policy. The shape of the curve helps us see how proximity to the terminal state (and the possibility of reaching it through Action 1) drives up the expected value.

3.5 Theoretical Properties of Value Iteration

Value Iteration exhibits the following theoretical guarantees:

- Convergence: The algorithm is guaranteed to converge to $V^*$ for any finite MDP with bounded rewards and $0 < 1$.

- Policy Derivation: Once $V^*$ is known, the greedy policy is optimal.

- Computational Complexity: For state space size $S$ and action space size $A$, each iteration requires $O(S^2 A)$ operations due to the summation over all successor states.

However, in practice, the applicability of DP methods is restricted by:

- The need for full knowledge of $P$ and $R$,

- Infeasibility in large or continuous state spaces (the “curse of dimensionality”).

These challenges motivate the use of approximation, sampling-based methods, and model-free approaches in reinforcement learning contexts.

3.6 Summary Table

The following table summarizes the key elements and tradeoffs of the value iteration algorithm:

| Property | Value Iteration (DP) |

|---|---|

| Model Required | Yes (transition probabilities and rewards) |

| State Representation | Tabular (explicit state-value storage) |

| Action Selection | Greedy w.r.t. value estimates |

| Convergence Guarantee | Yes (under finite $S, A$, $< 1$) |

| Sample Efficiency | High (uses full model, no sampling error) |

| Scalability | Poor in large or continuous state spaces |

| Output | Optimal value function and policy |

| Computational Complexity | $O(S^2 A)$ per iteration |

3.7 Conclusion

Dynamic Programming offers elegant and theoretically grounded algorithms for solving MDPs when the environment model is fully specified. Value Iteration, as illustrated, leverages the recursive Bellman optimality equation to iteratively compute the value function and derive the optimal policy.

While its practical scope is limited by scalability and model assumptions, DP remains foundational in the study of decision processes. Understanding these principles is essential for extending to model-free reinforcement learning, function approximation, and policy gradient methods.

Future posts in this series will explore Temporal Difference learning, Monte Carlo methods, and the transition to policy optimization. These approaches lift the strict requirements of model knowledge and allow learning from interaction, thereby opening the door to real-world applications.

Of course. Here is the provided text with detailed explanations added below each code chunk.